HE WHOLE POINT of the Brébeuf Hymnal is fabulous congregational singing, and the editors advocate “German Style” (unison with organ). On the other hand, many choirmasters add variety by singing some hymns with SATB parts, and that’s where the Choral Supplement comes in. 1 Singers and conductors who have experienced the Brébeuf harmonies have expressed admiration for their flowing vocal lines, sensible tessitura, restrained chromaticism, and rich harmonies. We generally retained the “classic” harmonies wherever this made sense, making slight adjustments only when absolutely necessary. Many have requested information about the theoretical principles we adopted, and the article below is my attempt to respond to such requests—in spite of my own deficiencies as a musician, which I hope the reader will excuse.

HE WHOLE POINT of the Brébeuf Hymnal is fabulous congregational singing, and the editors advocate “German Style” (unison with organ). On the other hand, many choirmasters add variety by singing some hymns with SATB parts, and that’s where the Choral Supplement comes in. 1 Singers and conductors who have experienced the Brébeuf harmonies have expressed admiration for their flowing vocal lines, sensible tessitura, restrained chromaticism, and rich harmonies. We generally retained the “classic” harmonies wherever this made sense, making slight adjustments only when absolutely necessary. Many have requested information about the theoretical principles we adopted, and the article below is my attempt to respond to such requests—in spite of my own deficiencies as a musician, which I hope the reader will excuse.

Some say music has no rules. They believe harmony is totally subjective, and counterpoint by a nine-year-old is “every bit as valid” as the counterpoint of Sebastian Bach. But the Brébeuf team rejects that assertion. We hold that the “Common Practice Period” followed certain conventions which can, indeed, be studied and known. Furthermore, we believe these “rules” were put in place—and embraced by so many composers—because they create music which is singable, interesting, and beautiful. In other words, the Brébeuf team believes such conventions have a “sonic justification.” That doesn’t mean every hymn composer rigidly followed every single rule. Nor does it mean—and we shall have to repeat this often—that every rule has the same weight or importance. My own personal belief is that one should not memorize rules; instead, one should train one’s ear to recognize beautiful voice-leading. This requires years of study, but the ear (eventually) becomes a reliable guide. I highly recommend a method developed at Northwestern University called: “HARMONIC READING: An Approach to Chord Singing.”

We will exclude musically absurd examples from the past:

* * PDF • “Musically Reprehensible” (Catholic Hymns)

With a few exceptions, the examples below come from hymnals esteemed by all serious musicians. Having explained a particular convention, I usually give an example which “breaks” the rule. This is not an attack; rather, it reminds us that “for every rule there is an exception.”

One final point: There’s a big difference between ignorance of the rules and “going beyond” the rules. Contemporary composers are not bound by “Common Practice Era” principles. Composer Kevin Allen, in #778 of the Brébeuf Hymnal, shows how a composer can deliberately “go beyond” the conventions of a former age. I was present when Mr. Allen’s hymn was sung during Sacred Music Symposium 2019—setting a text in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary by St. Robert Southwell, a Priest-Martyr whose poetry was admired by Shakespeare—and it thrilled everyone in attendance to the point that some began weeping. The recording cannot do justice to the experience of singing with that many musicians:

Avoiding Incomplete Chords

Except where they serve a specific purpose, the Brébeuf harmonies avoid incomplete chords. We frequently had recourse to what my professors called the “Bach maneuver”—where TI resolves to SOL instead of DO. (We remember that TI has a strong desire to resolve to DO.) Hundreds of examples could be cited, and we will examine a few, starting with Bach Chorale #17 (“Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag”):

Notice how Bach’s maneuver is used no fewer than four times! Moreover, the following example (“Das walt’ Gott Vater und Gott Sohn”) demonstrates that Bach is keen on his maneuver even when it causes “hidden” fifths between Bass and Alto—to say nothing of all voices moving the same direction (normally frowned upon)—because a sensitive ear avoids incomplete chords:

Sometimes, the Bach maneuver solves voice-leading problems. The Alto going to D would be impossible in the following example—“Waltham” from Hymns Ancient and Modern (1972)—since it would cause parallel octaves between Bass and Alto, but Bach’s maneuver solves it:

George Ratcliffe Woodward—in his marvelous Songs of Syon (1910)—harmonized “Freuen wir uns all in ein” using the Bach maneuver:

Similarly, when Woodward reproduces a Bach harmonization, such as “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland,” he retains the Bach maneuver:

Woodward also has recourse to the Bach maneuver when he harmonizes “Louez Dieu tout hautement” on page 142 of Songs of Syon (1910):

The leading Roman Catholic hymnal of its time, Aundel Hymns (1905), uses the Bach maneuver on page 326, with a melody by Caspar Ett:

I find it remarkable that Bach has no problem resolving TI to MI in Chorale #103 (“Nun ruhen alle Wälder”)—called by its more familiar name of “Innsbruck” in the Brébeuf Hymnal—even allowing the Alto to cross the Tenor, as well as “hidden” fifths between Tenor and Bass:

Parallel Octaves: Never Allowed

Musicians agree on very little. The choices made in the Brébeuf harmonies are not “the only correct way.” Other approaches are also valid. Yet there is one thing all musicians agree on: parallel octaves are forbidden in “Common Practice Era” hymnody. I’m only aware of one hymnal which embraces parallel octaves: the so-called “Traditional Roman Hymnal” printed by the SSPX circa 1999. (N.B. There’s nothing “traditional” about its harmonies.) In its pages, we find examples such as this:

Without trying to come across as mean-spirited, I can only describe the SSPX usage of parallel octaves as “grotesque”—especially instances such as this:

Even in beloved hymns, such as “Come, Holy Ghost,” the SSPX hymnal contains parallel octaves and parallel fifths—even between outer voices:

With the exception of the SSPX hymnal, parallel octaves are scarce as hens’ teeth in any decent hymnal. If one spends hours searching, they can be found once in a blue moon. An example would be the Episcopal 1940 Hymnal, #347 (“Hyfrydol”):

The following example, although not a hymn, comes from the Saint Michael Hymnal (2011). It is a Mass setting by “Michael O’Connor, OP” supposedly based on Mendelssohn, but the slew of voice-leading errors in the accompaniment struck me as remarkable—including parallel octaves:

George Ratcliffe Woodward (Songs of Syon) should have brought the Tenor down to F in “O Mensch, sieh wie hie auf Erdreich,” which would have fixed his parallel octaves:

I don’t consider the following example (#393 from the Episcopal 1940 Hymnal) to be genuine parallel octaves, since it occurs over the barline:

Some professors of music theory consider the following to be wrong. They argue that the suspension does not, in fact, eliminate the parallel octaves. (If it were a cut-and-dried 2-1 suspension, I would agree—but moving immediately to a diminished vii6 “disguises” the parallel octaves as far as my ear is concerned.)

Johann Sebastian Bach, in the following example, does something Orlando de Lassus also enjoyed: voice crossing to avoid parallels. (A respected Protestant hymnal, Hymns Ancient and Modern, does the same thing for BEDFORD.) Technically, it’s “legal”—but a sensitive ear still hears the parallel octaves:

There’s an old saying: “Even Homer nods.” The great Dr. Theodore Marier seems to have missed these parallel octaves when he wrote a harmonization to “Now Thank We All Our God” in Hymns, Psalms and Spiritual Canticles (1983):

When it comes to the Brébeuf harmonies, I know of only one instance of parallel octaves, but it’s by a contemporary composer—so it doesn’t really count. That’s because composers writing in a modern style are not bound by conventions from the “Common Practice Era.” For the same reason, we can’t be certain these parallels from the Pius X Hymnal (1953) constitute an error; because it’s a modern harmonization. By the way, for obvious reasons, examples such as this don’t count as parallel octaves. The Nova Organi Harmonia (NOH) uses parallel fifths all the time—and even parallel sevenths—but never parallel octaves.

Forbidden Vocal Intervals

The Brébeuf harmonies were created according to principles that make them sound sensational when sung SATB. The vocal lines were written according to established principles, which generally match the melodic rules of Johann Joseph Fux (Gradus ad Parnassum), such as:

•| Legal Skips: Legal skips are 3rds, 4ths, 5ths, ascending minor 6ths, and octave leaps.

•| Large Leaps: Leaps of an octave or minor 6th must be preceded and succeeded by notes within the leap (i.e. approached and left by contrary motion).

•| Melodic Compensation: The rule of “melodic compensation” says it is preferable to precede and/or follow a large skip with a step (or skip) in the opposite direction.

The issue of parallel octaves was black and white, but when it comes to “legal” intervals for vocal lines, gray areas abound. For example, descending sixths—which can be difficult to sing and don’t occur in plainsong melodies—are frowned upon. However, they aren’t exactly rare in even the best hymnals. Consider #76 (“Coblenz”) in the New Westminster Hymnal (1939):

The 1972 edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern has a descending sixth in #543 (“Bristol”):

The Episcopal 1940 Hymnal has an ascending sixth followed by motion in the same direction for #253 (“Luebeck”). For the record, it’s a peculiar passage because the Tenor and Bass have “hidden” fifths, and then the Bass leaps over the Tenor:

The 1972 edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern has a descending sixth in #287 (“Woolmer’s”), as well as ending poorly with an incomplete chord:

A dishonest person might pretend I said descending sixths are “impossible” to sing; but I said no such thing. I did say they’re difficult to sing, and you can see this by having your Bass section attempt to sight-read #163 (“St Flavian”) in the New Saint Basil Hymnal (1958):

Descending sixths pop up quite frequently in the Chorales of Johann Sebastian Bach:

Let’s move on from descending sixths and talk about other forbidden intervals. It goes without saying that if an “illegal” interval is found in the tune itself, nothing can be done. We must simply accept it. I have in mind something like #284 (“Windsor”) in the Episcopal 1940 Hymnal. The Soprano leaps a forbidden interval—viz. a diminished fourth—and then continues in the same direction. It’s quite peculiar, but makes “sense” in a certain way:

Speaking of “Windsor”…a very wonderful hymn tune is called “St George’s Windsor”—and its harmony is never altered. Even books like the New Westminster Hymnal (1939) and the New Saint Basil Hymnal (1958) don’t modify its harmony, even though they make adjustments to practically every other harmonization. The harmonization is remarkable, because it contains forbidden intervals, such as a tritone (in the Tenor) and an augmented fifth (in the Bass). In another section, all the voices move in the same direction:

Horizontal tritones are forbidden, yet can sometimes be found in respected hymnals. Charles Lewis’ New Vesper Hymn Book (1877) contains a tritone leap in #20 (“Erhalt Uns, Herr”):

A tritone—not to mention a whole slew of doubled thirds and incomplete chords—can be observed in #376 (“Down Ampney”) from the Episcopal 1940 Hymnal, which took the harmony from the English Hymnal (1906):

There is a beautiful hymn called “Jesu Leiden, Pein und Tod”—also known as “Jesu Kreuz Leiden und Pein” and “Er nahm alles wohl in acht”—which contains a descending tritone, followed by motion in the same direction:

The forbidden skip of a 9th is found in #258 (“Richmond”) printed in Hymns Ancient and Modern (1972), to say nothing of the horizontal 7th in the melody:

When Dom Gregory Murray reproduced Sir Richard Terry’s harmonization for “Vater unser im Himmelreich”—which he calls “Psalm 112”—for the New Westminster Hymnal (1939), he missed something. The harmonization has the Tenor end on E-Natural and begin on B-Flat, a tritone away. That’s almost impossible to sing in tune:

Speaking of “Vater unser,” the harmonization in Hymns Ancient and Modern (1972) is quite beautiful, but contains two tritones. I truly don’t understand the tritone in the Alto; moving to F would eliminate the tritone and the doubled third:

A peculiar harmonization to a beautiful tune is “Love Unknown.” Among other things, it has a tritone in the Alto—possibly done intentionally to “disturb”—which is faithfully reproduced on page 194 of the New English Hymnal (1986):

Frequently, an “illegal” interval is used to avoid excessively low notes for the Bass section, and a good example is from the New Saint Basil Hymnal (1958), where the first four Bass notes of “Corona” were transposed up an octave from the original, when the entire piece was simultaneously sunk to allow congregations to sing the melody comfortably:

Johann Sebastian Bach, in “Schau, lieber Gott, wie meine Feind,” has the Tenors sing a tritone:

In Chorale #170 (“Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland”), Bach gives the Tenors two tritones:

In Chorale #223 (“Ich dank’ dir, Gott, für all’ Wholtat”), Bach wrote a diminished seventh:

In Chorale #72 (“Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort”), Bach wrote an augmented fifth in the Bass (an outer voice!):

Don’t be surprised to find an occasional “forbidden” interval in the Brébeuf harmonies, especially when the harmonization comes from Bach. On the other hand, those who attempt to harmonize hymns should remember what my professor used to say. When somebody would say, “But Bach did such-and-such,” the professor would respond: “You’re not Bach.” Forbidden intervals should only be used for a specific purpose…and only after sufficient reflection.

Avoid Doubling The Third

Whenever possible, the Brébeuf harmonies preserve the “standard” harmonization for each hymn. Sometimes, a “standard” harmonization did not exist. Contrariwise, for certain hymns (e.g. “St George’s Windsor”) the same harmonization was used by every hymnal and never modified in any way. Perhaps the most common reason harmonizations were modified had to do with excessively low Bass lines, such as the way “Ewing” was printed on page 392 in the Catholic Hymn Book (London Oratory, 1998), a topic we will discuss below.

While doubling the third of the chord is not strictly forbidden, it should be avoided. Doubling the third destabilizes the chord: it’s best to double the root or the fifth. Furthermore, too much third sounds ugly and unbalanced to the sensitive ear due to priorities of the overtone series. (Indeed, it’s remarkable how little “third” one needs for an orchestration.) It’s also difficult to tune a chord with a doubled third. Exceptions to doubling the third include the diminished chord and the deceptive cadence.

The following example, from the Catholic Hymn Book (London Oratory, 1998) demonstrates how the editor desired the beautiful g-minor chord, but needed to double the third to avoid parallel fifths between Tenor and Alto:

On page 374 of Hymns Ancient and Modern (1972), we find Jerusalem the Golden set to a tune called “Ewing.” For the record, the tune’s range would be considered by some choirmasters as excessive. A doubled third is used:

In my view, there is no satisfactory way to avoid doing that—even though it creates “hidden” octaves between Tenor and Soprano—because moving the Tenor into unison with the Bass would lead to an augmented Second. The following solution doesn’t really “solve” the problem, yet would be considered by some an improvement:

The New Saint Basil Hymnal (1958)—in a way many feel was both excessive and unwarranted—tinkered with all the hymn texts and harmonizations in their book. Sometimes the “improvements” are bizarre. Consider what they did to “Oriel” on page 126, with doubled thirds galore and a severe case of “wanderitis” highlighted in green:

Sometimes it’s hard to understand why editors excessively double the third. Consider “St Anne” as found on page 217 of Hymns Ancient and Modern (1972):

It would have been easy to avoid doubling the third in several of those instances. Incidentally, the pink lines indicate “hidden” octaves and “hidden” fifths.

In a certain organ interlude by Dom Gregory Murray, I’ve always wondered why he doubled the third. He was such a magnificent composer, he surely knew better. When I play that one, I always “fix” it by playing an F instead of a D.

Bass Notes Excessively Low

An experienced director knows that some ideas look terrific on paper but don’t work in real life. The issue of excessively low Bass notes is a good example. A century ago, many hymnals were designed for choral singing—SATB—meaning the Soprano lines could freely soar up to high notes. When hymnals began to be focus on congregational singing, hymns were often transposed lower, allowing the Soprano line to be sung by the “average” person in the pews. However, this often creates problems for the Bass section.

Page 94 in the Catholic Hymn Book (London Oratory, 1998) contains a problematic Bass line for “St Theodulph.” Even if several of your singers are capable of “croaking out” those low notes, the tone quality will be poor, rhythmic accuracy will be lacking, and the volume will be very soft compared to the other voices:

It is strange, quite frankly, to observe that choice, because the Catholic Hymn Book was edited by the great Patrick Russill (b. 1953), who carefully avoids low Bass pitches; cf. his treatment of the 2nd half of “Crüger.”

The Peoples Mass Book (WLP, 1964) frequently has the opposite problem, allowing the Soprano lines to go as high as F# and G, which no congregation could sing well:

Number 632 in the Glory And Praise Hymnal (OCP) has ill-considered Bass notes throughout their arrangement of “St Columba,” which might be one reason so few choirs sing SATB from that collection—although the descending minor 6th is surprisingly easy to sing:

The “choral edition” of the Adoremus Hymnal (Ignatius Press, 2011) is quite odd. For example, in #471 (“Potsdam”), notice the perplexing way the Alto and Tenor lines suddenly become half notes. The Bass notes dip down way too low for balanced SATB singing:

Sevenths Must Resolve Downward

A very famous hymn is called “Eventide,” and appears on page 720 of the New English Hymnal. No matter where this tune this appears—and it appears in tons of famous hymnals—the harmonies by Willam H. Monk (d. 1889) are never altered. 2 It contains a flagrant 7th that does not resolve downward, as it should:

Three possible ways to “fix” this passage occur to me. The first is probably the best. The second preserves the ii7 chord, but has parallel fifths—although they sound okay to my ear because they’re somewhat “disguised” by Soprano and Alto combining to a unison. The third option is fine, because the “hidden” fifths are with an inner voice—in this case, the Tenor—but my ear prefers the second for some reason:

Page 218 of the New Saint Basil Hymnal (1958) reharmonizes a famous melody called “Culbach,” but the editor fails to resolve the seventh correctly. It would seem the “color” of a seventh chord was desired, in spite of the improper resolution. My ear is not really bothered by it, although I wish he did not double the third of the chord highlighted by green (done to avoid parallel fifths):

Page 116 of the Saint Pius X Hymnal (1952), edited by Fr. Percy Jones of Australia, reproduces the harmony for “Highwood” exactly as Sir Richard Terry wrote it, including the improper resolution of the seventh:

In Chorale #11 (“Jesu, nun sei gepreiset”), Johann Sebastian Bach resolves the seventh improperly:

Sometimes Bach “broke the rules” on purpose, to illustrate something in the text. However, I believe that seventh might be a typo—because if the G-Natural quickly went to F-Sharp for an eighth note, the problem would be solved.

Parallel Fifths: Avoid Them

We have pointed out that modern composers are not bound by the conventions of the “Common Practice Era.” Contemporary composers frequently use parallel fifths, but traditional hymn harmonization conventions forbid them. They are rare in serious hymnals, but if one searches hard enough, it is possible to find a few examples. The Laudate Catholic Hymnal (Kansas City, 1942) contains parallel fifths on page 126 (“O Esca Viatorum”), even between outer voices. My ear is okay with the parallel fifths, but not the incomplete chord at the end—but others will undoubtedly disagree:

The Episcopal Hymnal (1940) has the following for “Lobe Den Herren” (#279)—but I don’t consider them truly parallel fifths, because they happen across a barline:

Page 920 of the New English Hymnal (1986) contains parallel fifths in “Praise, My Soul, The King Of Heaven,” but they occur in the accompaniment, so they don’t really count:

Some authors allow what is called “unequal fifths”—when a Diminished Fifth moves in the same direction to a Perfect Fifth. Page 114 in the New Westminster Hymnal prints the “unequal fifths” from Sir Richard Terry (d. 1938):

The Episcopal Hymnal (1940) allows “unequal fifths” for #780 (“Westminster Abbey”), although it robs the melody of the beautiful syncopation in the original anthem by Henry Purcell (d. 1695) as explained by a footnote in the Brébeuf Hymnal on page 230:

Mozart Counterpoint Rules

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart summarized the rules of counterpoint in a brilliant way: “One voice goes up, the other down; one voice stands still, the other moves.” For hymnody, one should try to avoid having all voices move in the same direction. An example of all voices moving in the same direction would be page 126 of the Laudate Catholic Hymnal (1942):

On page 87 of the New Westminster Hymnal we encounter a peculiar harmonization by Dom Gregory Murray (d. 1992), one of my favorite composers. Murray has the Soprano leap to a dissonance (C-Natural)—at the same time allowing all the voices to move in the same direction—and the result is open to criticism. It’s not easy to understand why he didn’t have the Bass line skip to Middle C, which would have solved several problems:

The seventh entry in the English Hymnal (1906) contains an absolutely splendid melody called “Helmsley.” The voice-leading is puzzling, since all the voices move in the same direction simultaneously, and the editor doubles the third in two chords:

While I certainly hesitate to challenge Ralph Vaughan Williams (d. 1958)—whose renown and musical genius is not questioned by anyone—it’s difficult to understand why he didn’t do something like this:

Number 52 in Songs of Syon (Woodward, 1910) has a very strange harmonization for “O Mensch, sieh wie hie auf Erdreich.” All the voices move in the same direction twice, including the Bass leaping over the Tenor. Adding insult to injury, we find parallel octaves:

The Episcopal Hymnal (1940) has all the voices move in the same direction simultaneously—causing “hidden” fifths and octaves—for its sixth entry (“Bristol”), but it doesn’t bother my ear because it happens at the beginning of a new phrase:

My ear hates the incomplete chord ending the piece…but you already knew I was going to say that! We have seen—in the early example of “Das walt’ Gott Vater und Gott Sohn”—how Johann Sebastian Bach had such a dislike for incomplete chords that the great master allowed all voices to move in the same direction simultaneously!

Miscellaneous Items

Unlike the Renaissance, “Common Practice Era” hymnody does not permit open chords. It was surprising to see George Ratcliffe Woodward in #38 (Songs of Syon, 1910) use an open chord:

The use of 6/4 chords is absolutely forbidden; yet a flagrant one can be found in Hymns Ancient and Modern (1972) on page 550 for a melody called “St Mark” (Long Meter):

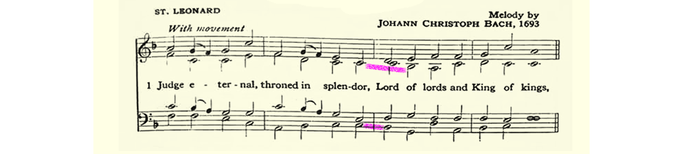

The only time a 6/4 chord is allowed is the so-called “cadential” 6/4. The following example (final measure) gives an example, although the voicing strikes me as atypical (because normally scale degree 5 would be doubled). By the way, we have spoken very little of the “horizontal” conventions for hymnody, and someday I’d like to write an article dealing with those. Apropos of horizontal considerations, #518 in the Episcopal Hymnal (1940) harmonizes “St Leonard” with all the voices simultaneously moving in the same direction. It is difficult to understand why the editor didn’t move the Bass A-Natural an octave down—especially since it skips over the Tenor line—but it would seem the answer comes from a “horizontal” consideration: viz. avoidance of two Perfect Fourths in a row:

Sometimes, one encounters something so wacky in hymnody, there aren’t any “rules” against it—one must simply let the ear be one’s guide. An example would be “Tempus Adest Floridum” from the Episcopal Hymnal (1940), which has the Soprano in unison with the Tenor while the Bass goes into unison with the Alto:

Sometimes, a particular composer will manifest a blind spot. An example would be Sir Richard Runciman Terry—a truly excellent musician in so many ways—whose hymn melodies often lacked strong harmonic rhythm owing to Bass lines repeating the same note over and over. Consider his harmonization for “Highwood,” or consider “Corona” on page 80 of the Westminster Hymnal (1912):

Another “rule” we must remember when we harmonize: Dissonances must be prepared. This is a tricky rule, and even “the best of the best” sometimes overlook it. Winfred Douglas (d. 1944) was quite respected as a musician—and justly so—but fell victim to an “unprepared dissonance” in #29 of the Episcopal Hymnal (1940):

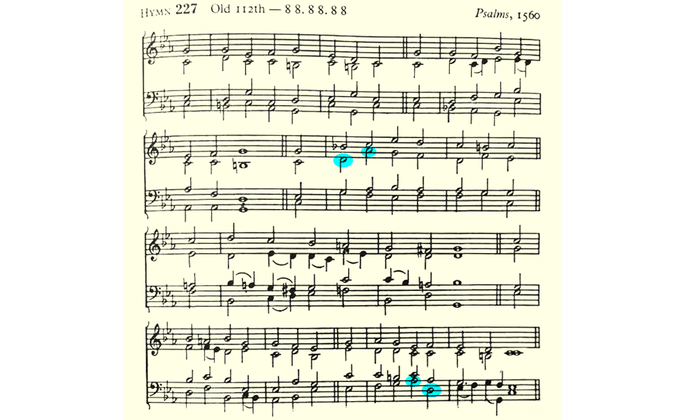

The editors of Hymns Ancient and Modern (1972) missed an unprepared dissonance in #227 (“Vater unser im Himmelreich”):

Examples of Nice Harmonies

It seems appropriate to mention a few hymn harmonizations which—in my opinion—display excellence. Full disclosure: I was deeply involved with the musical aspects of the Brébeuf Hymnal, so my observations are undoubtedly biased. Having candidly discussed the conventions of hymnody above, I’m sure certain readers will gladly “rip to shreds” the examples I give—but such criticism goes with the territory.

One of the hardest hymns to harmonize—without falling into retrogression and predictable chords—would be #724 (“Iste Confessor”). I am pretty happy with the version printed for the Brébeuf harmonies, especially because the Bass line “does the opposite” of the Soprano motion, which is pleasing to the ear. Several “hidden” fifths do occur, but they are generally concurrent with voices combining to a unison, which helps “disguise” them:

A marvelous hymn is #282 (“All Saints”)—whose melody is used for numerous texts in the Brébeuf Hymnal—but it contains a fair amount of “pitfalls” for composers seeking to harmonize it. I believe the Brébeuf solution is a decent attempt, if one can accept the ascending sixths in the Bass and a slightly boring Tenor line at the very end:

The Brébeuf harmonies for #659 (“O Heiland, reiss die Himmel auf”) contain bass lines that use marvelous descending stepwise motion—and we remember that the very best kind of bassline motion is stepwise, especially if it goes in contrary motion to the Soprano:

The Brébeuf harmonies for #875 (“Coelestem Panem”) contain “hidden” fifths, but that’s okay because they don’t occur between outer voices. At the green section (see below) the root of the chord should probably have been doubled. Instead, the fifth was doubled to avoid a sense of closure in the middle of the piece—but I now feel it would have been better to double the root or change the Bass to a half note on G:

Click here to listen to #875. (N.B. The melody is the same, but the text is different.)

I would like to end with a hymn by Richard J. Clark, #84 in the Brébeuf Hymnal. Mr. Clark is a contemporary composer, so he’s not bound by the “Common Practice Era” conventions we have been discussing. Nonetheless, his hymn has a nice emphasis on contrary and oblique motion. I didn’t mark “hidden” fifths over the words “our race” because the voices combining into a unison help to disguise them:

The name of the tune is “Seán.” As a modern composer, Mr. Clark is free to add the color of a seventh chord without resolving the seventh downward. Singers at Sacred Music Symposium 2019 sight-read “Seán” (used for several texts in the Brébeuf Hymnal) and here’s a live recording:

Reminder: No microphone can accurately capture choral sound, which is a “physical reality” and cannot be reproduced by computer speakers.

In my view, this melody proves that excellent composers can still write beautiful hymns—building on the “rules” of the past. Be careful, because once Maestro Clark’s melody gets stuck in your head, it never leaves!

NOTES FROM THIS ARTICLE:

1 The Choral Supplement is not meant to replace the “German Approach”—unison plus organ—but adds powerful variety by SATB singing for certain pieces. The Choral Supplement is marvelous, and has been praised by informed critics. Nonetheless, the normal way to involve a congregation in hymn singing is “German Style” (unison with organ).

2 Incidentally, this hymn—“Abide With Me; Fast Falls The Eventide”—demonstrates that even famous hymns sometimes have faulty Text-Melody correspondence. The first verse emphasizes the wrong syllables, but many Protestants have sung it since childhood so their ears have become immune. Another example would be #168 in the New Westminster Hymnal: the text corresponds quite horrifically to the melody. Many hymns, being strophic, contain defective verses—but these two are remarkable because the very first verse is flawed.